Details

Duration:

20'

Instrumentation:

vl vc pf

Commissioned by:

Performing Arts Fund NL

Dedicated to:

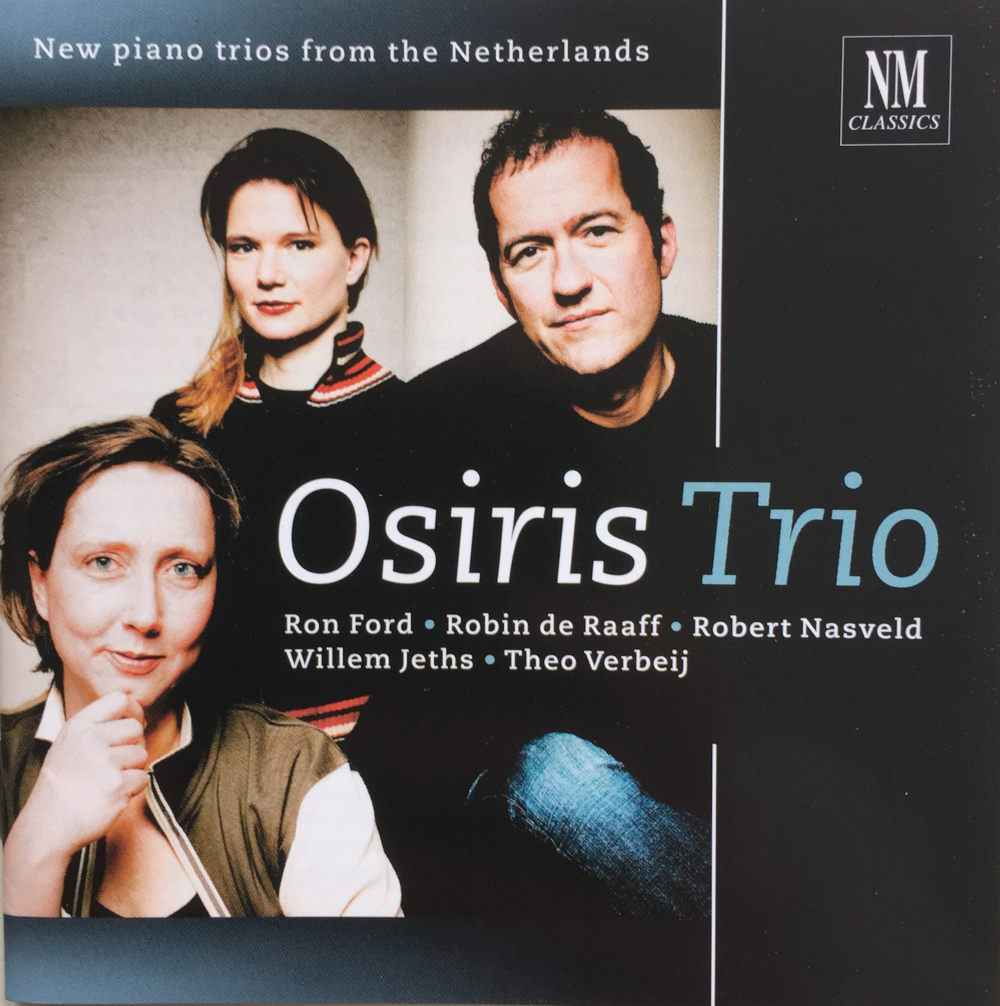

The Osiris Trio

Find on CD:

In Theo's Own Words

Let me say a few words about the individual movements.

The form of the first movement resembles a classical sonata form. The scale I used is a sort of Phrygian G major. The second subject is a quotation from the second act of the Zauberflöte by Mozart: the Choir of Priests which sings: “O Isis, und Osiris, welche Wonne!” Of course this is a reference to the Trio for which the piece was written. I tried to make the quotation blend into the whole movement instead of isolating it, so that people who don’t know the Zauberflöte also can enjoy the music. The second movement has a more abstract content in which various materials are juxtaposed according to the scheme: A B C A’. The third movement has the character of a scherzo with a small reference to early jazz. The motive from the first movement is used as basic material. The formal plan of the movement is A B A B’. The fourth and final movement has the same form as the second movement A B A’ B’ but has a severe and almost grim character and is, after the first movement, the longest.

I started working on my Trio in the summer of 1999, almost 13 years ago. The piece was finished in January 2000. Prior to writing this trio I had composed quite a few larger works for orchestra. This was the first time in ten years that I was writing for a small combination of instruments.

The process of writing was interrupted twice: the first time by a week of rehearsals and performances of my orchestral piece Alliage (1997) by the Concertgebouw orchestra conducted by Hans Vonk in November of 1999. The second time by a trip to the Huddersfield Festival for Contemporary Music in the United Kingdom where my piece Inversion (1987) for large ensemble was performed, also in November of that year. I decided to write a piece with the somewhat longer duration of about twenty minutes in four different movements: fast, slow, very fast and very slow. I also decided on the durational proportions of 7:4:3:6.

Personally, I usually do a lot of pre-compositional work on about three levels before the actual composing of a piece is done.

- Sketching motives

- Planning textures in concordance with the title

- Designing a time structure including rhythmic details

Let me elaborate:

1. Sketching motives is usually done with a specific context in mind. Usually this context is defined by a certain chord or, in my earlier works, in organizing the chromatic scale into twelve tone-rows, although usually they are in groupings of 2 to 4 notes. In the case of the Trio the faster movements I and III are written within the context of extended tonality. The slow movements II and IV use a different technique: the chromatic scale is divided into two groups of six pitches, called hexachords. I have derived motives and melodies for these two movements from these hexachords.2. Planning texture is done by making a list of possible combinations of instruments together with writing short examples for these combinations. I also use words, symbols and colors to describe them.

3. Designing a time structure including the detailed rhythm. For quite a while (since 1982) I’ve determined time-related phenomena like meter and rhythm separately from pitch-related phenomena like harmony and melody. This may seem strange, but it is actually a very old technique from the period known as the Ars Nova. A composer like Guillaume de Machaut used what is called a talea and a color. A talea is mostly a fairy long rhythmical pattern without pitch which starts to repeat itself after some time. A color is a melodic pattern without rhythm which follows the same principle. Of course when talea and color don’t have the same number of notes many interesting combinations may appear, purely by combining the two. The results may be highly unpredictable and random.

This brings me to the whole issue of chance and randomness in music. After John Cage, who showed that music written with random procedures may sound very much the same as highly defined serial music, composers did face a problem: how does a composer decide on the music he wants to write without relying entirely on his or her taste, without using either the rhythm and form of tonality or the free atonal or serial techniques?

My personal solution is the superimposing of numerical relationships resembling the so-called fractal in geometry. The mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot coined the word in 1975 when he strung a lot of earlier developments together. One of the basic traits of a fractal is the process of repeating features in a self-similar way on larger levels. This recursiveness is something we also know from traditional music theory like when we multiply 2 for musical form into the 4-bar halfphrase and the 8- and 16- bar period. We might also think of the modulation to the dominant as a higher level of the same thing as the secondary dominant of the dominant. What I do is to connect existing compositional techniques with the use of a certain degree of randomness tamed or limited by some numeral procedure. This results in very extended diagrams and sketches where only the meter, the rhythm and the grouping of bars into sections is decided. In this case, with the Trio, I decided to have a group of 4 numbers in a specific order which would determine the whole piece: 7:4:3:6. All 4 movements are subdivided by the same group of numbers, and so are the sections within a movement and the sections of sections, etc.

During the process of writing, the majority of decisions are made at the beginning and the amount of decisions gets smaller towards the end. Still there are a lot of possibilities to choose from. I consider choosing what you want to do and on what basis one of the biggest challenges in composition.

– Theo Verbey